How to Choose an Organic Fertilizer

Many products are marketed as “organic,” but consumers rarely know the differences in what’s actually in the bag. Certain fertilizers lend themselves better to an All-Natural Organic Turf Care (OTC) approach, while others work against it.

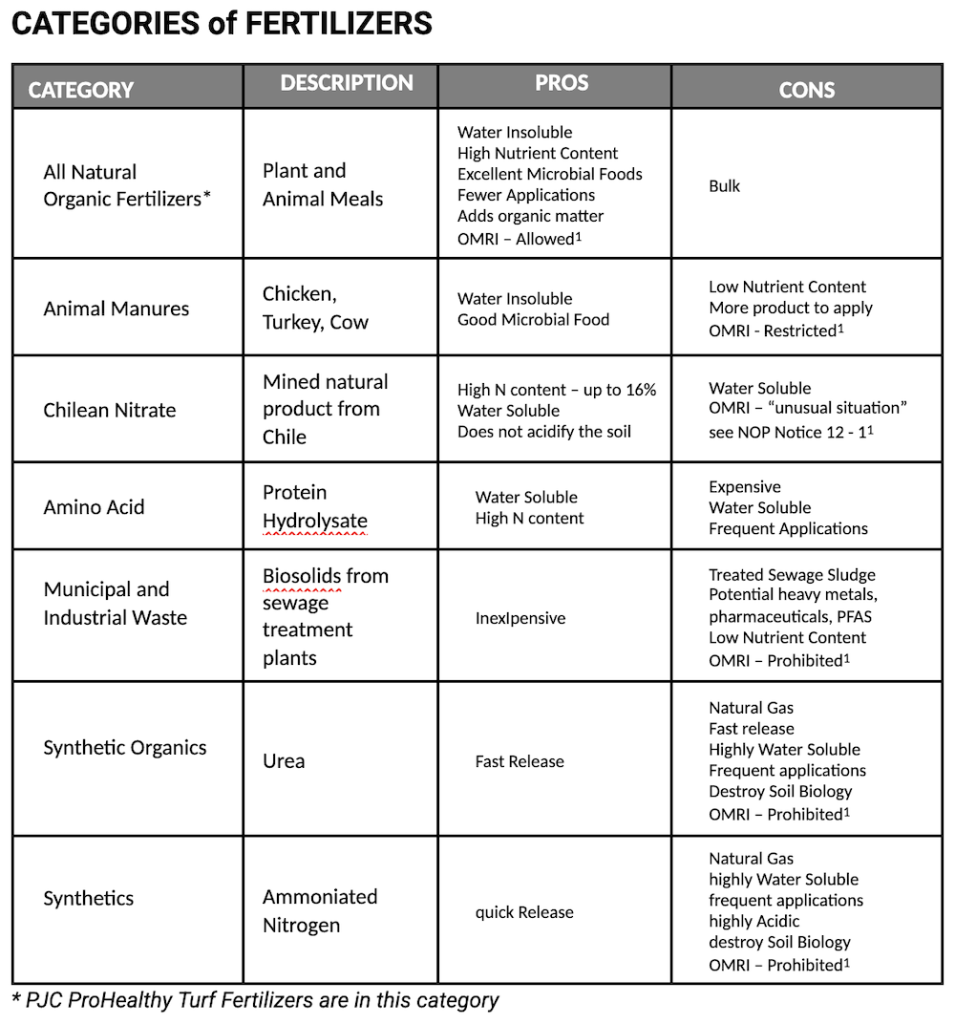

Fertilizers can contain ingredients from several categories, each with its own pros and cons. Below, we’ve outlined the major differences between organic fertilizer types and explain them in more detail.

Categories of Fertilizers

Fertilizers generally fall into several main categories. Each one impacts soil biology, nutrient availability, and long-term turf health differently.

All-Natural Organic Fertilizers (Plant and Animal Meals)

All-Natural Organic Fertilizers (like PJC’s ProHealthy Turf Blends) derive their nutrient content from plant and animal meals. Plant and animal meals are high nitrogen sources.

The cost-per-nutrient tends to be lower than other organic alternatives because these fertilizers have a high nutrient content. They have also been found to be excellent fungal and bacterial foods, which are critical in an all-natural program.

Although the bulk associated with natural organic fertilizers is often seen as a disadvantage, the benefit is that they add organic matter and valuable nutrients to the soil.

Animal Manures

Animal manures are a common form of organic fertilizer. There is often a low cost-per-pound because the base material is a waste product. However, manures also have a lower nutrient content, so the cost-per-nutrient tends to be high. To reach a target nutrient value, you need to apply more product, which increases both product and labor costs.

Manures are also high in phosphorus, which can increase seed germination in undesirable plants, leading to increased weed pressure.

In addition, poultry litter-based fertilizers may contain some level of copper and arsenic. Heavy metals can build up in the soil and create health concerns for consumers and runoff. Because of these concerns, OMRI restricts the use of these fertilizers in organic crop production.

Chilean Nitrate (NaNO3)

Chilean nitrate—also known as Natural Nitrate of Soda (NNS)—is a mined substance and is therefore classified as a natural product. It has an analysis of 16-0-0 and is considered soluble. NNS is available in cold soils and may be taken up directly by the plant without microbial activity. This may be considered a perceived advantage in Northeast soils.

The National Organic Program (NOP) and OMRI changed the restriction on NNS in place since October 2012. Now, production practices must maintain or improve the natural resources of the operation.

Chilean nitrate must be used sparingly since it is also a salt. When used excessively, it can negatively affect soil health.

Amino Acids

The term “amino acids” is somewhat misleading because all organic fertilizers derived from plant and animal meals contain amino acids. Amino acids are the building blocks of protein, which plant and animal meals already contain. Vendors often use the term “amino acid fertilizer” to refer to a class of fertilizers that are soluble in water.

These products are protein hydrolysates manufactured in one of three ways: enzymatic, acid, or alkaline hydrolysis of proteins. In effect, protein hydrolysates create a water-soluble organic nitrogen source that is available to plants. However, because the nitrogen is water-soluble, there is potential for nitrogen that is not taken up by the plant to leach.

There are times when these products may prove advantageous and times when they do not.

Municipal and Industrial Waste (Biosolids)

Biosolids are the output from municipal sewage treatment plants and are used as another form of fertilizer.

The potential inclusion of heavy metals and PFAS is the greatest concern with these products. These metals can come from industrial waste and prescription medicines. There is also concern about chemical contamination from household cleaners, antibacterial agents, and other substances poured down the drain. Because of these concerns, the Organic Foods Production Act (OFPRA) prohibits their use in organic agriculture. States have also begun regulating their use.

Effective July 1, 2025, the state of Connecticut is enforcing a groundbreaking regulation:

“No person shall use, sell, or offer for sale in this state any fertilizer intended for land application or soil amendment that contains any biosolids or wastewater sludge that contain PFAS.”

(PFAS Fertilizer and Soil Amendment Notice)

Also in 2025, the EPA stated concerns that PFAS in sewage sludge spread on pasture land are harmful to our health.

“Organic-Based” Fertilizers (Synthetic Organics)

A fertilizer can claim to be “organic” without being all-natural, as long as it contains carbon.

Urea is an inexpensive fertilizer and the most common form of synthetic organic. It is also often coated to delay the release of nitrogen and reduce burn potential. However, in certified organic farming, urea is not allowed. Urea—like other synthetic fertilizers—is a salt. The high salt index associated with urea negatively impacts soil biology by killing microorganisms. Salts also make it harder for seeds and plants to extract the water needed for normal growth. It’s also important to know that repeated applications of urea fertilizer can acidify soil, making it more difficult to reach the ideal soil pH for turf grass.

Synthetic Fertilizers

Synthetic fertilizers are chemically manufactured from refined minerals, petroleum by-products, or atmospheric gases (such as urea, ammonium sulfate, and mono-ammonium phosphate).

These fertilizers are highly water-soluble and designed to directly feed the grass plant. This can cause a flush of growth after application. Unlike organic fertilizers, synthetic fertilizers do not improve long-term soil health or soil structure. They can also harm beneficial soil biology.

There is also risk of striping, over-fertilizing, and “burning” the grass, along with increased potential for nutrient runoff into water sources.

Conclusion: Read the Fertilizer Label Carefully

Packaging can be deceiving. Just because a fertilizer claims to be “organic” doesn’t mean it is free from synthetic chemicals. If any of the numbers for N-P-K are higher than 12, chances are it is not an all-natural organic fertilizer.

When choosing an organic fertilizer, read the label carefully—or reach out to us!

Sources

OMRI – Organic Material Review Institute, www.omri.org

NOP – National Organic Program, www.ams.usda.gov